🌅 • on urbana, recurse, brooklyn, & distributed systems

brooklyn & recurse center

After roughly 2 and a half-some months of work, learning about the fundamentals of distributed systems in noisy cafés in Urbana, IL, then learning about the fundamentals of distributed systems at Recurse Center in Brooklyn, NY, while also balancing the dangerous act of being unemployed, having too much time, moving to a new city, and moving out of that new city fleeing the oncoming pandemic not even a month later back to the small town that I told everyone I would never come back to, I finished building the thing I originally intended to finish building . . . earlier. Along this journey I learned about the beauty of

- just how bad dollar pizza can be

- how important good logging is to debugging asynchronous systems

- the problem of distributed consensus

- when to avoid eye contact with people on the subway

- how to present technical & comedic content to an audience in an engaging way that lets my personality shine through (thank you Recurse Center nontech/tech talks/this blog)

- when to stare at people on the subway

- how to manage my own time efficiently, giving my all to learning things both technical and creative

- how quickly I could become absorbed into the world’s best cult (thank you again, Recurse Center)

I could’ve been much more efficient with my learning about distributed systems and building my distributed file system, but that wouldn’t have been any fun.

I wouldn’t have met so many amazing people who gave me the inspiration to pursue so many branching paths. Things like technical writing, speaking, or making blog posts tooting my own horn that only 3 people, who I explicitly begged asked to read it, will read.

I wouldn’t have gotten the experience of living in Brooklyn, something completely unlike anywhere I’ve lived before. A place where:

- you can get any food you want, but still end up only eating Japanese, peanut butter, and cereal for a month

- it always smells faintly of urine, no matter what the time of day or where you are

- amazing people are always within reach and always willing to talk

(Am I enumerating things too much? I don’t care. Nobody’s going to read this!)

back to urbana

I’m back in Urbana now. It’s warm again here. The sun sets later. It always smells of wood stoves, flowers, or bonfires, but not of urine. The people that I said goodbye to have forgiven me for the terrible things I did to them, thinking I would never return. We melt away the days together as we did before.

I can ride my bike for hours in the country and watch the sun set and the stars settle onto the clear sky, unobscured by tall buildings or the constant sirens and noise of ambulances and traffic, framed by tall prairie grass and endless open land.

My knees feel good. The ground here is soft. Not so much pain for me to worry about.

Squirrels chitter and bees buzz, wild chives grow dense in the grass in my yard and in public parks, I walk the same paths forever. Deer stand in the brush and watch me from far away.

Enough about Urbana! Who cares.

COMPUTERS! LOOK WHAT I’VE DONE!

Chord-ish De-Fish: thank god it’s over

After getting a rough grasp of distributed systems I threw myself off a tall cliff into the task of building a distributed filesystem.

My design required three separate layers, each of which I built from scratch and are coated in an alarming amount of my own blood, creaking from the rust that accumulated as a result of my tears and sweat getting all over them. They are listed in order of their role in the placing of a user’s file onto the distributed filesystem.

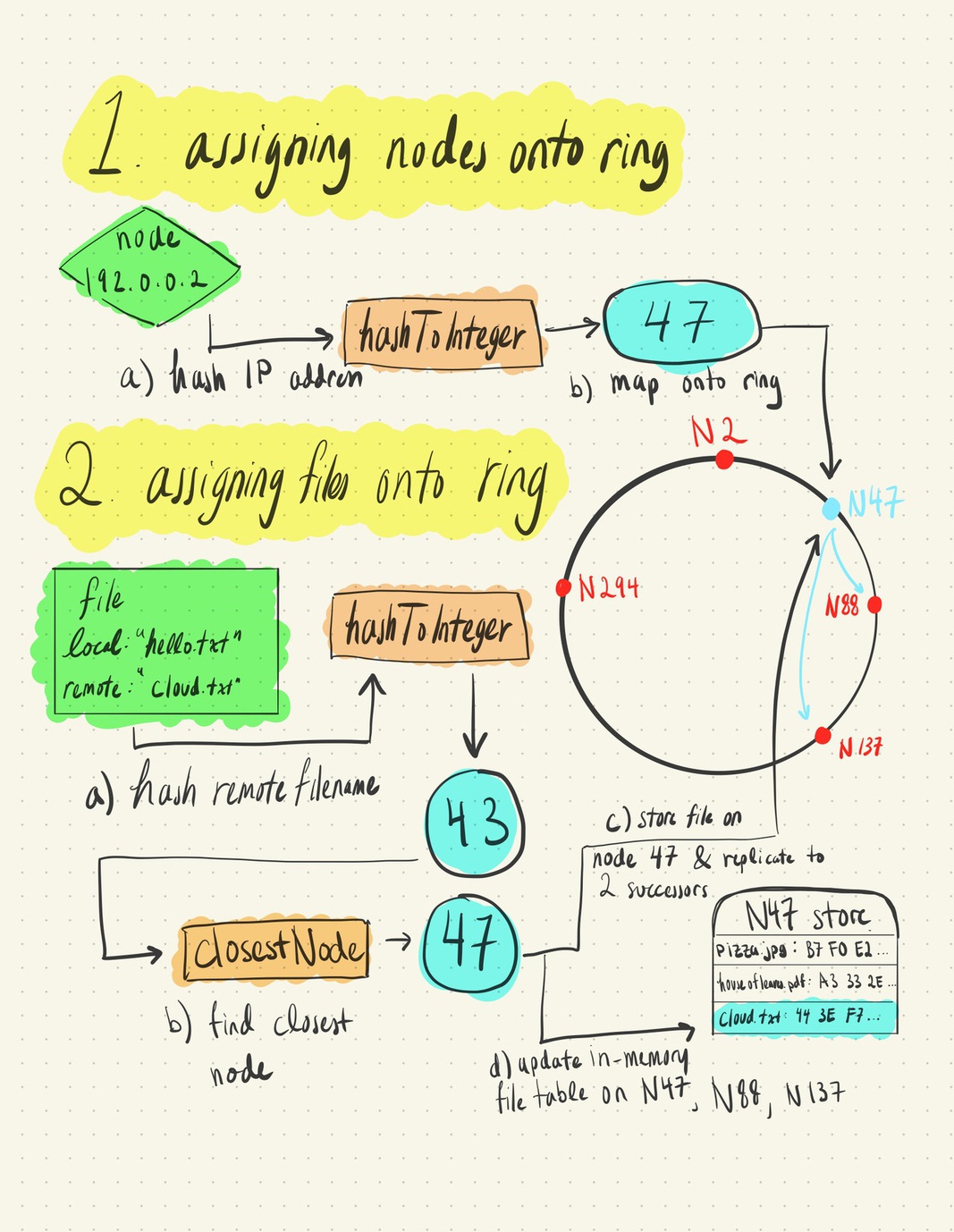

Chord-ish, the membership layer. The membership layer lays the foundation for everything by assigning nodes / servers in a network onto some “virtual ring”, giving them a distinct ID number as a function of their IP address. Then each node begins heartbeating to some number of nodes around it, setting up a system that allows them to gossip membership information and become aware of failures.

Leeky Raft, the consensus layer. A client sends commands, or entries to the consensus layer. These commands are similar to HTTP verbs. For example, the command to put the file

test.txtonto our distributed filesystem with the nameremote.txtwould be expressed as"PUT test.txt remote.txt". The consensus layer then replicates this entry to all other nodes in the network. On confirmation that the replication was (mostly) successful, they send the command to the filesystem layer.Chordish DeFiSh, the filesystem layer. The filesystem layer receives the command from the consensus layer and begins executing it. It assigns the file a distinct ID number as a function of their filename, using the same method as the membership layer. It then stores this file at the first node with an ID greater than or equal to its own. If no node’s ID is greater, then it wraps around the ring and tries to find a node there.

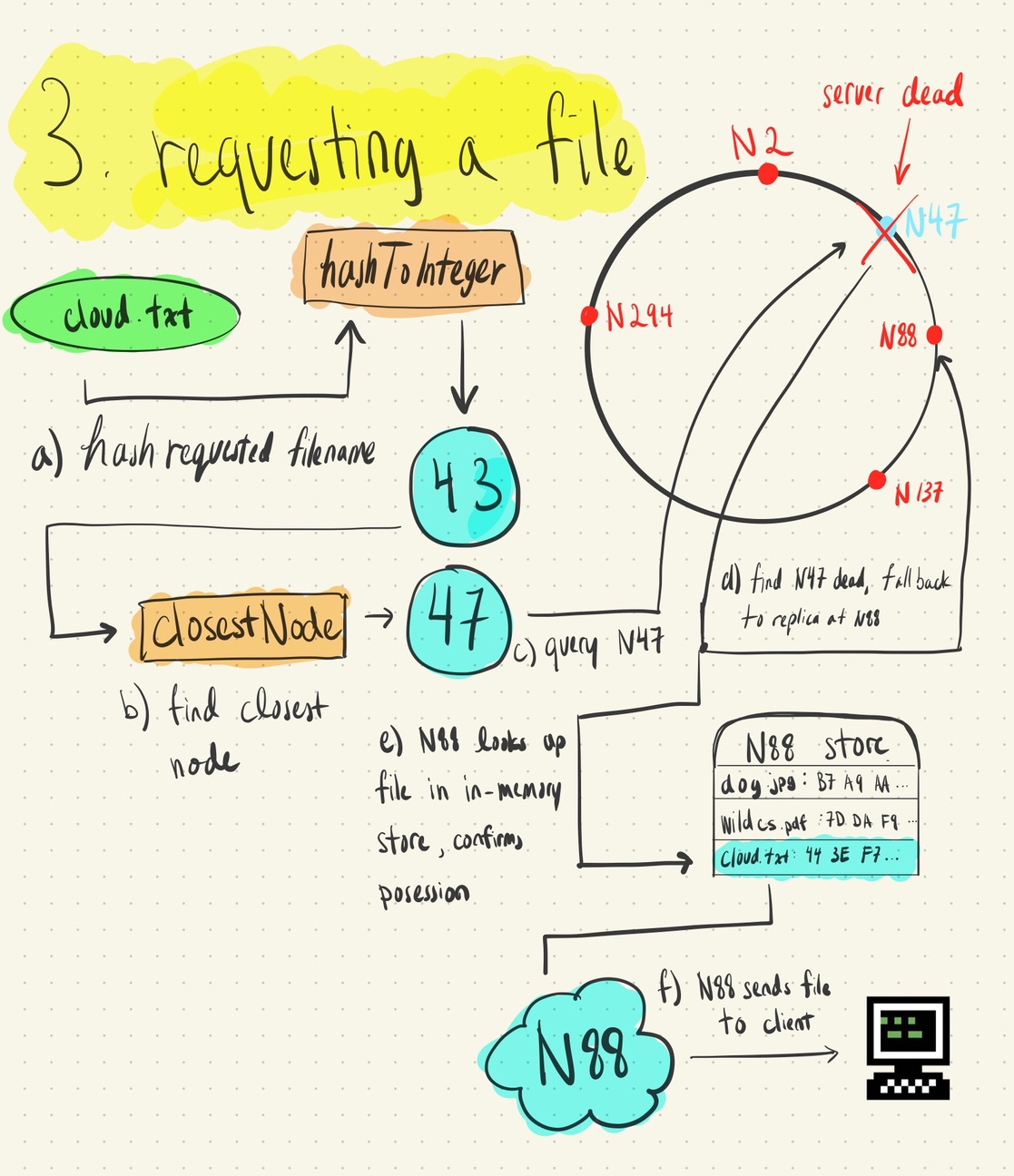

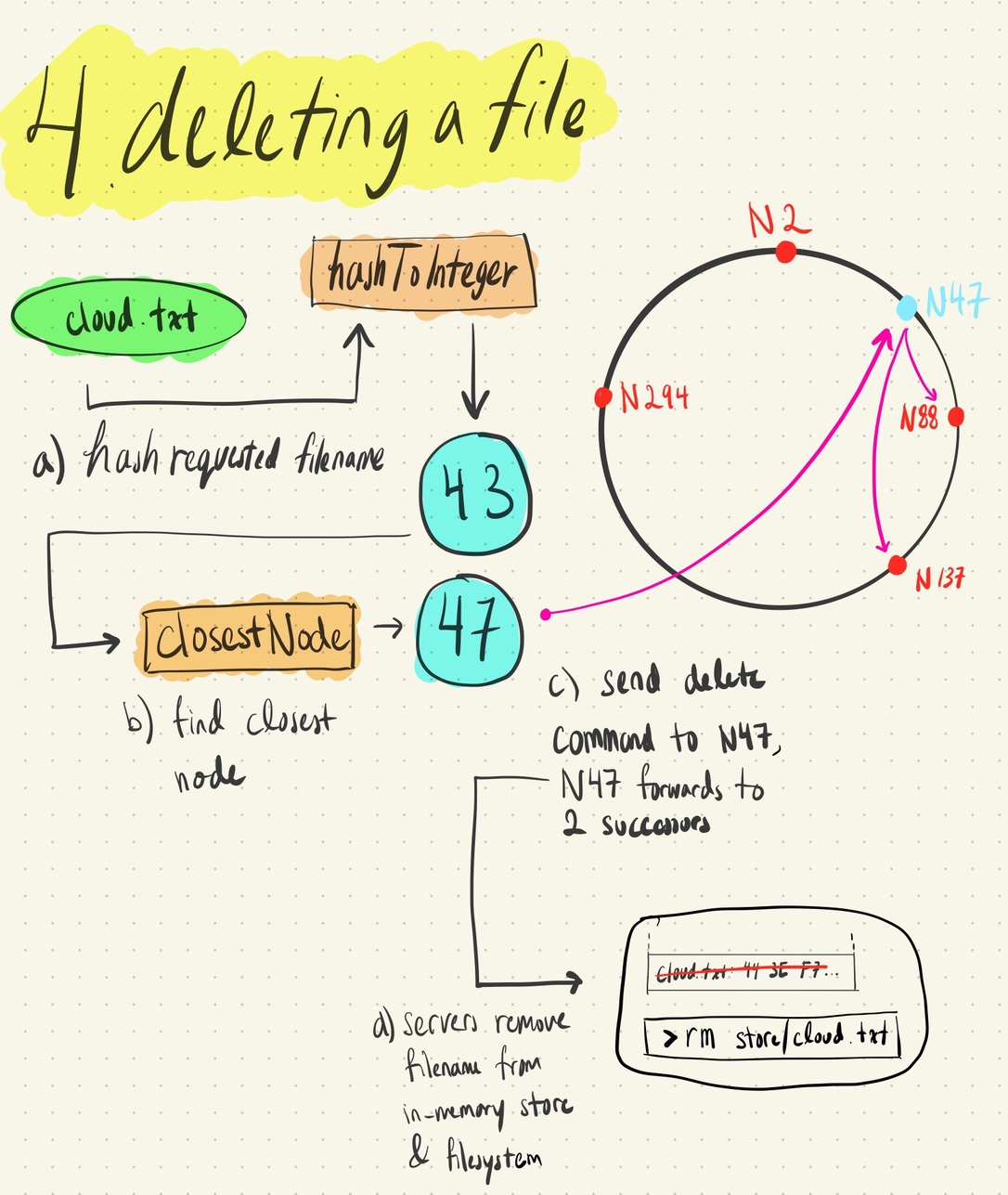

Files are replicated to the 2 nodes directly “ahead” of the aforementioned node. Files are stored as actual files in each nodes’ filesystem, and as

filename:sha1(file data)maps in the runtime memory of each Chordish DeFiSh process, as a fast way to check for file ownership & save time by ignoring write requests for a file it already has.From there, users can upload, delete, or download files from the file system. The visuals below will explain how this all works, sort of.

I emerge, covered in some strange fluid. I’m bleeding, although its not obvious from where. I haven’t eaten in days. . . . . *cough* *cough* “it’s over? it’s tolerant to some number of failures and nodes can recover from complete failures?” . . . . *cough* some blood comes out of my mouth *cough* “leader election works and clients are properly routed to the correct leader by non-leader nodes?” . . . . “nodes successfuly replicate files to their successors and file lookups on dead nodes are successfuly rerouted to those successors?”

. . . .

“finally . . .”

. . . .

git add -A && git commit -m “works lmfao” && git push origin master

. . . .

“I can die.”

. . . .

*cough* I die.