📷 • ultimate torture: creating a generative photo gallery

Preface

Before I quit my last job, I asked my manager for advice. Specifically, I asked him what he liked to see in engineers.

He told me that he likes to see people hacking at things, making complex systems work together rather than giving up and pursuing simpler tasks.

Now, whenever I catch myself about to make what I might consider a bad design decision, I think about his advice. Then I make the bad design decision. Every time, it’s a good time.

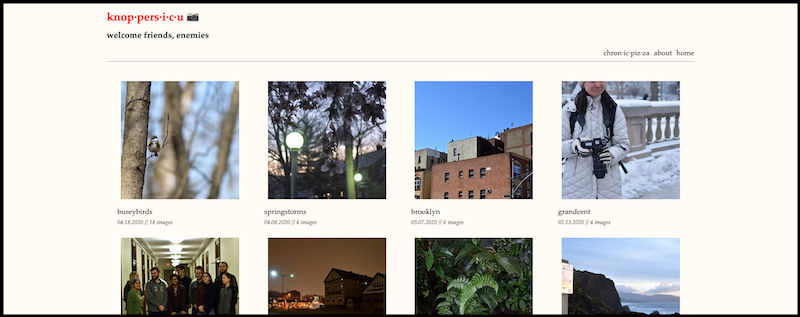

With that having been said, I made a new website! It looks pretty close to chronicpizza, but serves a very different purpose. It’s a programmatically generated photography archive.

Let’s talk about it.

First: the end product (to hold your attention):

People like visuals. Here’s a visual you dirty, impatient person. Now let’s talk about how this actually got built.

Why?

My normal photography workflow looks like this:

- Take photos

- Edit photos

- Upload photos to Google Photos

- Re-download those photos and size them down so I can use them as thumbnails

- Host those photos again on another site, but sized down versions

Steps 4 - 5 are pretty redundant and are actually a fair bit of extra work depending on how many photos I’m processing and what I want done with them. I don’t like those steps.

Sometimes, step 3 hangs indefinitely and I have to pick a careful combination of images and upload my entire album in batches. Which is annoying.

Also, Google Photos charges extra if you want to upload original, uncompressed JPEGs. This is doubly annoying. I don’t want to pay to retain image quality.

Google Photos also suffers from being a “modern” web application. It’s too fucking interactive. It looks great, but per-page visual consistency is not something that you get from Google Photos. Also, if I’m running something beefy like Docker, navigating through it becomes annoyingly slow. Sometimes it’s annoyingly slow even if I’m not doing anything.

Google Photos also can’t be used as a janky image host. It’s deliberately designed so that you can’t just consistently right-click -> copy image location. This contributes a lot to steps 4 and 5.

It does some things really well, but I really don’t need it to do most of those things, including letting it become familiar with the shape of my face, of my friend’s faces, my travel habits, hobbies, and other stuff that Google probably already knows about me.

Keeping this all in mind, I decided on a small set of requirements for my personal alternative.

- The web service should be responsive and fast.

- It shouldn’t require any upkeep or manual grooming besides uploading images.

- This website should be used purely for looking through a gallery, saying “I want these images”, and then getting the static URLs for those images to either download them or display them elsewhere.

And so began a number of sleepless nights and toiling with AWS.

New from AWS: T3 (Toil, toil, toil.)

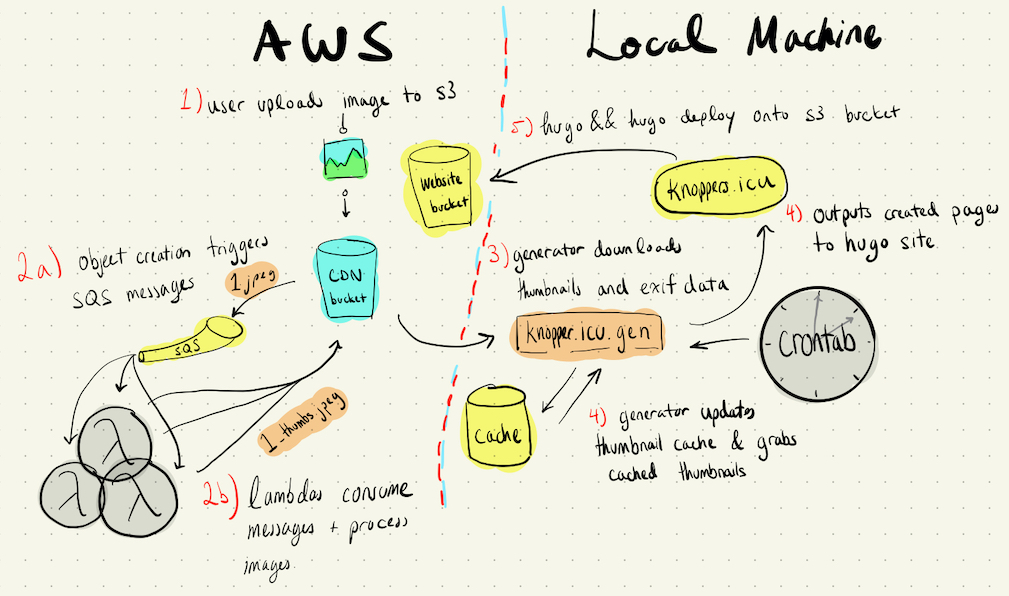

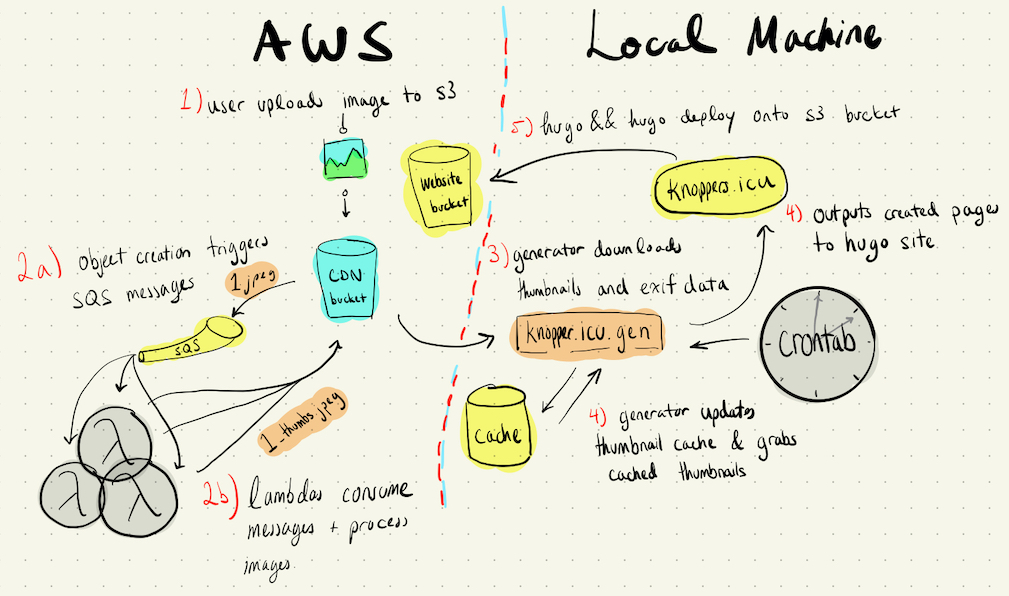

I decided to implement my idea with an s3 bucket as my data store and a lambda pipeline that would take images from that bucket and generate thumbnails for them. Uploading files to the s3 bucket was easy enough, with aws s3 sync doing pretty much all of the work for me. Processing them was a different story.

Lambdas are a wonderful idea. Lambdas were exactly what I needed and were free to use. Lambdas were a pain.

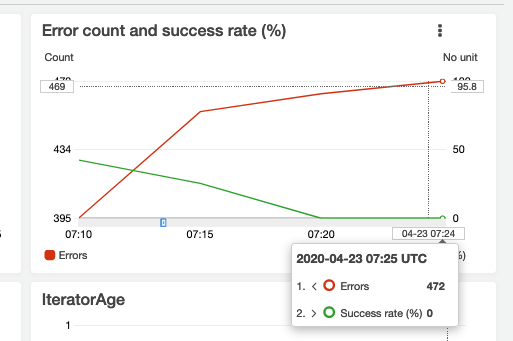

I first started by having a trigger call my lambda every time a file was created in my bucket. No good. AWS is a distributed system and with that comes plenty of quirks. My lambdas would constantly stumble over themselves due to inconsistent times between file uploads and lambda triggers. Sometimes they would be triggered pretty much immediately, sometimes it would take forever.

When they did start to work consistently, I realized that just telling my lambdas to do work on an entire bucket wouldn’t make sense because every object creation resulted in a trigger. They would step all over each others’ toes, forming a pulpy mess on the dance floor. I was misusing lambdas.

I disabled the s3 object creation -> lambda call trigger and replaced it with a s3 object creation -> simple queue service (SQS) message -> lambda call trigger, and things made more sense. My lambda could focus on operating on a single file, defined by the message from SQS, instead of operating on a whole bucket.

Still, there was substantial toe stepping. As well as vision loss.

Multiple messages were often sent per creation. Messages often had mangled object keys (which was easily fixed with urllib.parse.quote_plus, but how could I have known that?). Also, sometimes messages would be sent before the object had even been created. Those were fun. Although it seemed like adding a delay of 30s to SQS message delivery did the trick.

With AWS being a distributed system, it’s not that surprising that simple things could become so convoluted. It also didn’t help that there weren’t readily available examples of messages to use as mock data for testing.

I’m still too traumatized to talk about packaging the lambda up with all its dependencies.

Eventually though, with gratuitous logging and toiling, I got it working. Images uploaded to the s3 bucket now had accompanying thumbnails generated as fast as the images could be uploaded! Nice.

Please ignore my new bald spots and massive facial scarring.

Hugo, gogo, wait, no, stop, is this a bad idea?

Great! Now I have the backend. Here comes the fun part.

I decided to use Hugo as the web component. I love Hugo. It makes building and maintaining a snazzy website trivial (see www.chronicpizza.net). I’m not having to juggle 5000 random frameworks that will go out of date next week. Hell, I pretty much only have to write markdown, HTML and, sometimes, JavaScript.

Hugo generates static sites which are exactly what I want. They’re fast, simple, with consistent and predictable interfaces. It does this with markdown files and its native templating language. Better yet, deploying a static website with an s3 bucket is just a matter of uploading the index.html and enabling static site hosting on the bucket.

I thought for a while about how to have Hugo read from the s3 bucket and generate posts accordingly. Then I realized that’s probably a disgusting abuse of Hugo and decided not to do that.

Instead, I decided to make a disgusting abuse of Hugo with python, because then … I don’t know. I would use python and boto3 to scrape the s3 bucket and generate markdown files with unsafe html to plop into my Hugo site. From there, I could just do hugo build && hugo deploy and everything would be okay.

Which worked great! Except for certain things.

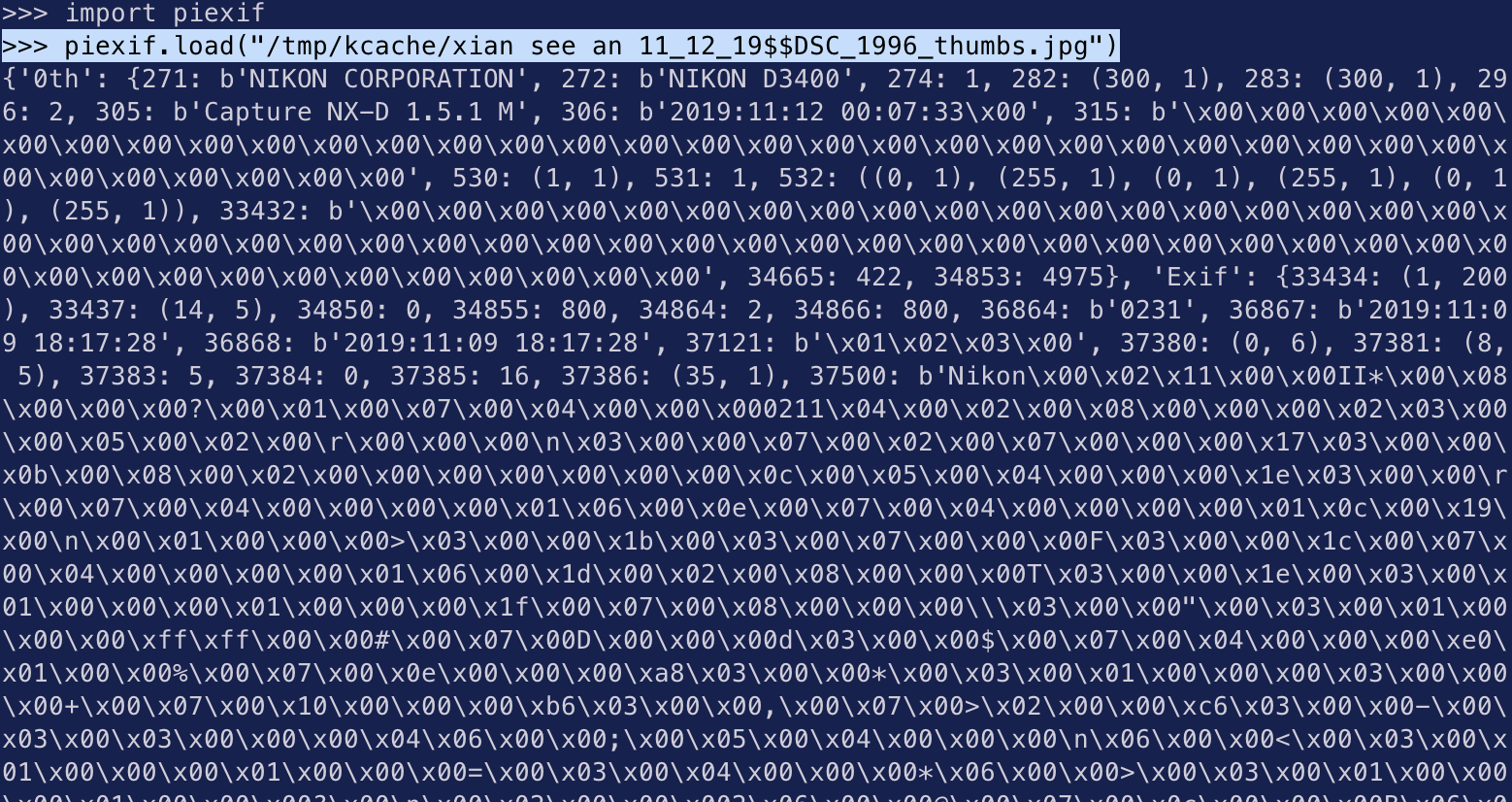

Turns out exif data, the data attached to images that tells you about how the image was taken (camera model, shutter speed, aperture, etc), doesn’t get preserved when you resize images. Like I did when I made the thumbnails.

Fuck!

I had to go back and redo that whole thing. Let’s not talk about it.

After I got the exif data back, I realized something else.

Exif data was not made for humans to read.

Also, exif data isn’t guaranteed to be consistent.

Also, parsing exif data is not good for you.

Thankfully, someone else on the internet has already suffered for me.

# parse_exif.py

# https://www.codedrome.com/reading-exif-data-with-python-and-pillow/ <-- this guy is my hero

Thank you, codedrome.

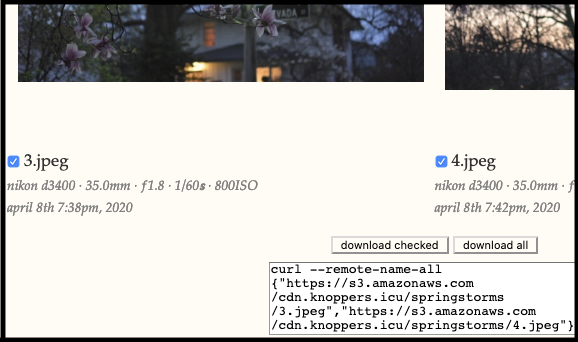

Next, I had to figure out how to let users download multiple files at once. This is usually accomplished by zipping them and downloading it as a single file, but that makes too much sense. So I just wrote a simple JavaScript function to create a curl statement instead.

I can’t say I’ve seen something like this anywhere else so at least I have that.

Kick me while I’m down, I like that

I had the page generation and Hugo deploying to s3 on my machine and decided it was now time to push this work onto my Raspberry Pi, as I do with my personal weather service and subscription mailing bot (which may have brought you here, but likely not, because I’m probably the only person who’s ever going to read this).

First, the ARM processor on my Pi prevented me from getting the latest version of Hugo, meaning I couldn’t hugo deploy. Well, no problem I thought. It’s no fun if I don’t have to do something hacky. I’d just write a script to deploy it manually.

Then it turns out my website’s theme wasn’t compatible with that version of Hugo, so I couldn’t even hugo build it.

This was too many degrees of hackiness, even for me.

I gave up.

Now it runs on a crontab on my laptop. Still works great; but I’m sad about not being able to build it on the Pi. Oh well.

So what did we end up with?

Conclusion

Now we have . . .

- A zero maintenance website with split-second deploys easily handled by a low resource cronjob

- Stupid-fast loading of large photo galleries (100+ images) thanks to my thumbnail preprocessing lambda

- The ability to have my photos accessible to normal people (and myself) online by just uploading to s3, and not having to do other stuff

- A reliable image host with static urls I can access with just

right click -> copy image location

It was a pain, but it was worth it.

It’s nice to have nice things.

git:

website: github.com/slin63/knoppers-icu

website-generator: github.com/slin63/s3-page-generator